![]()

Hurrah for Mr. Davis! Hurrah for Mr. Lincoln!

Part 1

by Shulamith Levey Oppenheim

by Shulamith Levey Oppenheim

Illustrated by Mary Flock Lempa

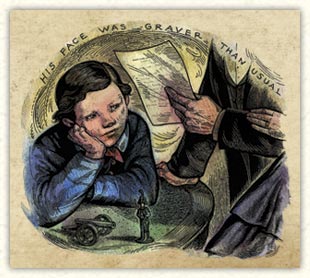

Pa held out a telegram. His face was graver than usual, these war days.

“Emilie is at Fort Monroe, in Virginia, with one of her children, Katherine. She refuses to take the oath of allegiance to the United States. The officer in charge asks me what to do.”

My father looked down at my mother, who stood holding his arm. Then he looked at me. His voice was as strained as his eyes.

Emilie was my mother’s half sister. She lived in the South, like many of Ma’s family. And what a problem Ma’s Southern relations have been for Pa, right from his being elected president “of all the United States,” as he’d say again and again.

No, it’s been more than a problem for Pa and Ma. It’s been a great ache in their hearts. I could see this, looking at each one looking at the other. Torn inside, they were. It’s terrible when a family takes sides, ’specially in wartime. Two of my mother’s half brothers already had been killed fighting for the South.

My mother’s pleading broke my thoughts. “Her husband, Ben, is just buried in Atlanta, Father. You know he died at Chickamauga. You must let her come here.” Ma put her head against Pa’s arm.

He smoothed her hair with his free hand. Pa was always trying to soothe her since my brother Willie died last year. He was eleven, a year older than I am now.

Times I feel it’s Pa needs the soothing even more. Not so long ago he told me he blamed himself for this war. “If I hadn’t been elected president, son, perhaps the South wouldn’t have broken away, and then we’d have none of these terrible killings.” But he told me he had to keep the country together.

“Nearly three years ago, Mother,” Pa said, “I offered Ben Helm a high post, paymaster in the army with rank of major. I begged him not to join the Confederacy. I admired him and have always loved your beautiful little sister.” He waved the telegram toward me. “What do you think I should do, Tadpole?”

I had to smile. Thank goodness Pa kept his humor. I was baptized Thomas, but my head was sort of large for my body when I was born, so I became Tad, short for Tadpole.

I looked at Ma who’d raised her head up from Pa’s arm and was looking at me, firm and sad. Then I looked at Pa who’d raised his thick, black eyebrows. I felt as divided as these United States.

“Well,” I began, and almost said how it’s mighty lonely here since Willie died. But I caught myself. I know I should catch myself more often. Right now, good thing I did.

“Well,” I started again, “I think Ma and Aunt Emilie would like being together, and I’ve never met Katherine. . . .”

“Then she shall come!” Pa lifted up Ma’s chin and bent to kiss her cheek. “I shall telegram immediately: Send her to me!”

I gave Pa a great bear hug round his legs. “Someday I want to be just like you, Pa.”

“But without such troubles, Tad,” Pa said, and he smiled just a smidgen. “Without such troubles.”

Ma hurried to the door. “Thank you, Father. It will be all right. You’ll see. It will be just fine.”

Pa flopped down on the sofa. With a sigh, he stretched out on the deep couch, something he did after a long day of meetings at the War Office. Ma begged him, “Please slow down, Mr. Lincoln,” but he was always running back and forth to the Telegraph Office to get up-to-the-minute reports of battles, and troops, and the number of wounded. We all worried about Pa’s health, and Pa worried about ours. Made a circle, it did.

Pa gave one of his great sighs. “I hope your mother is right, Tadpole.” He motioned to me to sit beside him. I settled on the floor with my back against the sofa.

“People get strange ideas in wartime, son. You and I know how your mother has been slandered by both sides. The Confederates say she’s betrayed her Southern roots, and our Union says she’s a spy in the White House for the South.” Pa chuckled and rolled his eyes. He could make his face do anything. “Your mother, a spy! I’d soon call your goat Nanka a spy!”

Pa mussed my hair. “But I have a piece of advice for you. When Aunt Emilie and Cousin Katherine come, stay away from the subject.”

“The subject, Pa?”

Pa swung his legs onto the floor and sat up. “The subject of our divided country and our divided family. Emilie is devoted to the South, and so must be Katherine, even at six years old. We want their visit to be a pleasant one.” Pa gave a push off the sofa and straightened his jacket. “Why, I remember when Emilie was a young girl, and mighty pretty she was, your mother and I gave her a white velvet bonnet with flowing white plumes. Very smart.”

I jumped up. I’d never heard Pa speak about ladies’ clothes before.

“So,” and I could hear a command in that word, “so, Tad Lincoln, I rely on you to help make Katherine and her mother’s visit a comfortable, enjoyable one. Is my confidence well placed?”

I nodded. Though truth to tell, holding my tongue was not what I did best.

-----

The next afternoon, Ma called outside my door, “Hurry, Taddy. The carriage is waiting.” We were going to Harwood Hospital. Ma visited wounded soldiers almost every day. I’d gone with her before, but mostly to the Convalescent Camp in Alexandria, where sick soldiers rested and recovered.

She smoothed her skirt as we clip-clopped toward the hospital. “It’s so important for me to deliver the food and flowers myself. Most of those soldiers are mere boys. Their suffering faces break my heart.” She drew me close to her. I guessed what she was thinking. Willie had died from the fever, and Robert was twenty, just right for the war. That is, if anyone is just right for getting shot at, getting killed.

As we stepped out of the carriage, a nurse came running down the steps. She took up Ma’s hands and kissed them. “Oh, Mrs. Lincoln, I’m so glad you’ve come. The hospital carts brought in dreadfully wounded soldiers last night. The surgeons haven’t stopped operating and amputating since the minute those poor souls were taken in.”

The nurse whispered something in Ma’s ear, and Ma looked down at me.

“Tad,” my mother crouched down in front of me, “many of the men are having their arms and legs amputated. They can’t help screaming out, with nothing to ease the pain except whiskey and a nurse to wipe

the sweat from their faces.”

I straightened my shoulders as far as I could without tipping backward. “Pa’s going to take me to the front one of these days. I’m coming with you, Ma. Pa would want me to.” Then I waited by the door.

Ma stood up and took my arm. And we went in.

-----

It was dark and December cold when we started back. Ma tucked her green plush carriage robe round our legs and up to our waists. I laid my head against the thick sleeve of her coat. It was warm and smooth.

“I never imagined gunpowder and bullets made such, such . . .” I couldn’t find the words for the awful things I’d seen. Eyes blown out. Stomachs torn open. Bones sticking out of bodies. I’d heard groans and screams and prayers and cries of “Help me!” and “Please let me die!” coming down on us from everywhere.

Ma was whispering, “Your Pa didn’t want this, Taddy. How he tried to avoid this terrible war. ‘It will be bloody, Mother,’ he said again and again. ‘Brother against brother. Cain and Abel, Mother.’ ”

“The Confederate wounded must be in the same awful way, Ma. Aunt Emilie’s and Cousin Katherine’s people. Same screaming and dying.” I was glad she couldn’t see my eyes. I rubbed my cheeks with my sleeve. “Why, Ma?”

“The Union has to stay together. Your father swore to this. But nothing he said or did kept the South with us,” Ma took a deep breath, “even assuring the Southern states he wouldn’t touch slavery, an abomination he hates.” She patted my hand. “Now, let’s talk about Emilie and Katherine’s visit.” She moved a bit away from me, and I sat up. “I’m sure you already have plans to keep your cousin busy. I’m so looking forward to hugging Emilie again and hearing news from home. They’ll both be sad, Taddy, very sad. Losing a husband and father, and brothers.”

Ma could hardly say that last word. Hers, too, they were.

-----

Next morning when I came down to breakfast, Ma and Pa were already at the table. Ma smiled at me over her teacup.

“They’ll be here tomorrow, Taddy. Good morning.” She reached for Pa’s hand. “I’m so excited, Father. To see Emilie again. And to meet Katherine. And to have news of home. I wish the other two children were coming. It’s been,” she closed her eyes, then opened them wide, “why, it’s been years since we’ve seen each other, since she was eighteen.”

I filled my bowl with oat porridge, my favorite, covered the top with sugar, and sat down next to Ma. I noticed Pa squeeze her hand, but he sure didn’t look as happy as she did.

“It won’t be easy, Mother, keeping our lips closed while our hearts are open.”

My! I set down the creamer and stared at Pa. My! He did have a way of putting things just right. That’s exactly what I’d been worrying myself sick about. Keeping my lips shut tight while I was hankering to know what was in my cousin’s heart. Her pa dead in the war, and she and her ma far from home. I get such an ache round my heart. Last night I had a horrid dream. I wanted to run into Ma and Pa’s bedroom just to be sure they were both there.

“Poor Cousin Katherine and Aunt Emilie.” I wiped my mouth with my napkin. “They’re going to be mighty sad, Ma.”

“Your mother is well aware of that, son. I’m glad you are, too, though I’m not surprised.” Pa stood up. “I must be downstairs in the War Office. Heaven knows what news is in store for me this morning.” He kissed Ma, ruffed up my hair—as always—and was gone.

Ma rolled up her napkin and pushed it through a wide, silver napkin ring. It was decorated with an M in raised silver—for Mary.

“I’m having a few ladies in for tea, Tad. Finish your lessons. Pay attention to your tutor and don’t worry this one so. Keep busy. I’m going to the hospital now. Someone sent over a case of wine, and I want those poor, sick men to have it as soon as possible.”

Truth was, Ma and Pa never touched alcohol. Truth, too, even if they did, she’d be taking the wine over to the hospital. From what I saw yesterday, wine was as good a medicine as any.

After Ma left I ate two pieces of bread loaded with honey. Ma and Pa loved learning and books, but I hated studying. Here I was, ten years old and I could hardly read, let alone write. My brother Robert was at Harvard College, but he’d failed his exams first time round. Willie’d been the prize pupil. Poor Ma and Pa!

I was on my way to find my tutor—I couldn’t even remember his name since I got a new tutor almost every day, well, every week, maybe—when I decided I really didn’t want lessons. So I went straight to my room to check on my goats. Yes, sir! There they were, spread out on my bed, chewing away on a couple of old rags I’d given them, happy as can be.

“Good old Nanka, good old Nanny.” There wasn’t much room, so I curled up at the end of the bed. I loved the munching sounds they made.

Next sound I heard was the lunch bell about taking my ear off.

“Stay right there.” I blew a few kisses to my friends, smoothed my hair, and tucked in my shirt. “I’ll be back, and then we’ll plan some special treats for Cousin Katherine.”

to be continued

copyright (c) 2009 by Shulamith Levey Oppenheim