![]()

Hurrah for Mr. Davis! Hurrah for Mr. Lincoln!

Part 2

by Shulamith Levey Oppenheim

by Shulamith Levey Oppenheim

Illustrated by Mary Flock Lempa

After lunch Jip followed me back to my bedroom. I bent down to hug him and kissed his nose. “You are the spoiltest dog in Washington, Jip.”

And he was. Most all lunches he sat on Pa’s lap, smacking his lips and gobbling down the tenderest pieces of meat and chicken, being petted the whole time. “These little creatures know more about us than we know ourselves,” Pa told me more than once. I believe it. And I’m pretty darn sure Jip is the best comforter Pa could have for all his troubles.

Nanny and Nanka were still on my bed, chewing old rags. When I came in, they looked up at me as if to ask, “What now?” I’d been wondering just that, about what to do with Cousin Katherine. I remembered all the fine times I’d had with Willie. Now there was just me left. But, oh my, the things we did. Like bombarding the Cabinet Room with toy cannons. “I tell you, Jip, it took the Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy, my pa, to get everyone quiet again. Did those grownups jump! And the fun we had in the attic! Lots of clothes to dress up in, old spectacles, sleds ... ”

I looked at Nanny and Nanka. Jip leaped onto the bed and nuzzled in beside the goats. “I could go up there and get a sled and hitch it to both of you and Jip could ride. ...”

I plopped down on the floor. Suddenly I was feeling sad. Really sad. Nanny and Nanka and Jip were good friends, but I still missed ...

I felt a tug at my sleeve. It was Jip, wagging his tail like crazy.

“You’re right, fella. Let’s see if goats are as good as ponies.” I looked ’round my room. “How about my chair? That’ll make a dandy wagon, good as a sled. And rope. Where’s my rope? I always keep rope—never know when you’ll need rope. Pa must have told me that.” Now Jip was yipping and yapping, and Nanny and Nanka were off the bed, nibbling at the fringe of the bedspread that my grandmother’d given me back in Springfield.

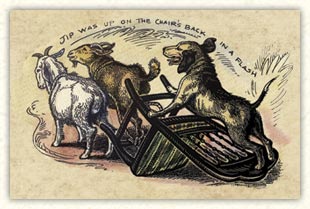

I found two stout pieces of rope under my bed. Didn’t take but a wink to fasten the goats to the chair, turned over so I could hold on to the legs. Jip was up on the chair’s back in a flash. I didn’t even have to tell him, just point. And we were off!

Oh, I was feeling much better. The chair made a loud clatter going down the stairs. I could tell the goats were enjoying themselves as much as I was. They were bleating, and Jip was barking.

We whipped through the hallway past the State Dining Room. As we came along toward the Red Room, Ma’s favorite parlor where she entertained her friends, the door must have been a mite open. The smells of those cakes and sandwiches must have come straight into the goats’ noses, ’cause they changed course and charged into the room.

“Whoa,” I yelled. I dropped the chair legs and leaped forward to catch my trusty steeds, but it was too late.

Jip jumped into the lap of a lady with a

hat like an eenormous serving tray, with crimped brown ribbon all twined about and a yellow rose. Nanny and Nanka ploughed right across the room into the tea table. How those cakes and sandwiches flew high into the air, only to come down again onto Ma and the ladies and me and Jip and the goats. What screeches! And what munching!

“Thomas Lincoln, what is this?” Ma was picking a bit of crumb cake from the lace on her chest. Her cheeks were very red. Mine must have been red, too.

“I’m sorry, Ma. I was trying out something new, to give Katherine a specially good time. I’ll bet she loves goats.”

“You round up these ... ,” she waved her arms at my animals, who were having a grand tea party of their own, “these creatures. Your Pa will have a word with you later.” Then she turned to her guests who were in quite a state.

I didn’t hear what she said, I was so busy getting the chair righted so I could drive the goats back upstairs. But I hoped Pa would remind her of what he always said, “Let the children have a good time.”

“It was great fun, wasn’t it, Jip?” I whispered to him as he jumped back and sat proud as you please, licking his lips all ’round with his long, pink tongue.

Later that evening Pa and I were alone in the family room. Pa was curled into his favorite armchair with those long, long legs of his hung over the side. There were worn spots on the heels of his wool stockings.

I stood still as I could beside the chair. Pa stared at me for, maybe, a few seconds. Ma had told him about my adventure, and I had the feeling he was doing his best to look very stern.

“You probably should have stayed upstairs with your—what did you call it, son?”

“My test, Pa. I was testing to see whether I could hitch Nanny and Nanka to a cart to take Cousin Katherine for a ride when she comes. Using goats instead of ponies, you know, to make her laugh, Pa.” I tried not to smile myself, remembering those ladies jumping and screaming, and holding on to their hats and those little bags all covered with beads on long chains they carried everywhere. It was a sight!

Then an ever-so-small smile began stealing ’round the corners of Pa’s mouth and eyes. He reached out, and I tucked myself close against him on the edge of the chair. I waited. He’d gone very quiet. Then he said softly, “I’m really sorry, Taddy.” Then he was quiet again. I waited. “I’m really sorry I missed it. It must have been a sight. A real sight!”

Aunt Emilie was dressed all in black, with a shiny pin shaped like a bird at her neck. She did look sad. And so thin. My cousin Katherine held tight to her Ma’s hand. She wore a wool cape, and thick stockings, and high button shoes—all black, too. And they both had on bonnets with black veils.

For one second, when they stepped down from the carriage, I thought—or maybe felt—that Ma and Pa gave a kind of start. But only for a second. Then they were hugging each other and crying, and hugging and crying. Ma took Aunt Emilie straight to her room. Pa swung Katherine up into his arms and carried her to our parlor to be by the fire.

Since early morning I’d been repeating to myself, “Lips closed, hearts open.” I wanted to ask Pa and Ma, were they worried, too, that something might slip out about the war and us being Union and them Confederate. I didn’t, but I’m sure they were real worried.

Ma and Aunt Emilie had lunch together, just the two of them. Me and Katherine and Jip and Pa ate in the second-best parlor.

“Well, well, little Katherine.” Pa heaped potatoes and a slice of roast chicken dripping with gravy onto her plate. What was Pa going to say? He gave a bit of chicken to Jip, who was in his usual place on Pa’s lap.

“Well, well,” he said again, then he looked at me across the table, raising those bushy eyebrows high onto his forehead. “I do believe Tad has some mighty fine adventures planned for you. Do you like animals, dear Katherine?”

My cousin hadn’t said two words since she’d come. Now she was sitting still as a brood hen, staring down at her plate, silent.

“Yes, sir.” I could barely hear her. “Ah got a dawg an’ three cats an’ ... ” And then she burst out in tears. Quick as a wink Pa was out of his seat, throwing Jip to the floor, and he had Katherine on his lap, her head buried in his shoulder. I had a stone in my belly. She was a miserable girl!

“It’s all right, little Katherine.” Pa was stroking her hair. “Cry all you want. Cry all you want.” He straightened the bow at the back of her neck that was holding her curls. They were reddish brown and mighty pretty.

I came ’round to Pa’s chair. Just how do I talk to a girl six years old? And give her a good time? And not mention the war and her Pa? I could feel my tongue tying up, but it was my turn.

“There’s lots to do here, Katherine. I’ve got two goats called Nanny and Nanka, and a pony, and a turkey called Jack, and two white rabbits. There’s Jip, and goldfish in the water lily tank in the conservatory. And Pa gave Jack a reprieve, so he’s not going to be our Christmas dinner.” I was out of breath.

“Speaking of goats ...” Pa put a finger under Katherine’s chin and turned her head away from his shoulder. He wiped her cheeks with his napkin. “What do you think of this goat?” And would you believe it, Pa moved his jaw side to side, and he stuck out his chin, and opened his eyes to nearly bulging, and he gave out the loudest goat noise I’d ever heard.

We all said Pa’s face had to be made of rubber, but he hadn’t done anything like this since Willie died. Watching him now made me realize how much I’d missed funning with him. Made me think how we were all pretty sad, too. And here we were wanting to cheer up Aunt Emilie and Cousin Katherine. Well! If Pa could be commander in chief of this war he hates, then I’d better get busy.

Katherine was staring at Pa. I’d like to say she was smiling, but I don’t think she was.

Pa didn’t seem to mind. “Now,” he set her back on her chair, “finish your lunch. I have to get back to the wa—,” he gave a deep cough, “back to my office. I’ll see you children at dinner.”

There it was! Already! Even Pa couldn’t help a slip. So what was a chatterbox like me gonna do?

After Pa left, Jip made a leap onto Katherine’s lap. He wasn’t big for a foxhound, but most of him hung over the sides of the chair, she being so slight.

“He’s naice.” And straight away she was stroking his ears. I liked the way she said “nice.” Naice. It was soft, right from the South.

I rubbed Jip under his muzzle. “Pa says animals know more about us than we know ourselves.” Jip sure knew something about my cousin. I’ll bet he could tell just how sad she was and was wanting to help.

“Pa had a piglet when he was a boy, and when it grew up, he rode it just like a horse. Can you see my Pa with those long legs and dangly arms riding a pig?” This time I know a tiny smile was playing round my cousin’s mouth.

Well, this was a start. I felt in my pocket for my pocketknife.

“Ever see a pocketknife?” She shook her head. I pulled out the blade. “It’s grand to have. You never know when you’ll need a knife for cutting string or whittling wood.” I thought of the war map Willie and I had cut into a table when we first got our knives, but I couldn’t show that to Katherine. Well, right now she seemed to be happy with Jip, and he was in heaven, with his eyes shut tight, almost purring.

I closed the knife and put it back in my pocket. Looking down, I saw my Union Jack badge stuck right out on my collar. I looked at my cousin. She had her cheek close to Jip’s nose and she was humming to him. I turned and fair tore that badge off, stuffing it into my jacket pocket. Law! Wherever I looked there were things to remind us of the war.

Just then Ma and Aunt Emilie came in. I ran up to Ma, trying to put a “Help Me” sign on my face.

“I’m going to show Aunt Emilie parts of the White House and a few of the state rooms in the East Wing. She thought Katherine might like to come. What about you, Tad?”

That’s Ma! I’ll bet she suggested taking Katherine along.

“Thank you, but I think I’d better see to the goats and ponies. Then tomorrow I can show them to Katherine and maybe take her for a ride.”

Katherine looked up. “Ah thought you said y’all just had one pony.” And without thinking, I answered, “That’s right, Cousin Katherine. I do have one pony. The other one belonged to my brother Willie.” Law! I could have died right there. I stuck a fist into my mouth, but of course they heard me. Next thing Aunt Emilie put her arms around Ma’s waist and hugged her close. Ma put her head against Aunt Emilie’s shoulder.

“Come along, Katherine.” Aunt Emilie stretched out her hand, and then she looked straight at me and gave me the kindest, saddest smile. I know those smiles. Pa’s always smiling that way these days.

When they left, Jip was at Katherine’s heels. Pa’ll be right proud of Jip when I tell him.

I took off for the animals. The goats had been sent outside to the pen after the fuss yesterday. “They’ll be company for the ponies,” I had told Mr. Watt, the gardener. I was hoping he’d give them a bit of attention, him being around the grounds most of the day. But Mr. Watt wasn’t too keen to care for my animals since I’d eaten most of the strawberries he’d been saving for a state dinner. How was I to know not to eat them if he didn’t tell me? And the goats had a taste for his flowers.

When I went into the street there were lots of Union soldiers passing by. And prisoners, too—Confederate, of course. And wounded. People said Washington was one big hospital now. How can we take Aunt Emilie and Cousin Katherine out riding without reminding them of the war? Yes, sir, I’d better speak with Ma tonight.

to be continued

copyright (c) 2009 by Shulamith Levey Oppenheim