![]()

The Star Shard

Part 6

by Frederic S. Durbin

by Frederic S. Durbin

illustrated by Emily Fiegenschuh

Throughout the afternoon, Cymbril’s gaze strayed toward the drab valley spreading below, the air above it crossed at times by heavy-looking crows. Some dead trees at the nearer edge had hardened and whitened in the sun, resembling stacks of bones.

By evening, her flower garland had begun to wilt, sooner than she’d hoped. She thought again of the old man’s toothless smile when he draped the necklace over her head at the market in Fencet. She’d watched some of the Rake’s crafters press flowers in frames or inside books, later arranging them into pictures made entirely of dried, flattened blooms. Cymbril could try that if she had even one book of her own. But she had no possessions except for the jeweled hairpin from her mother and the blue-green Star Shard that had belonged to her father. Her clothes, comb, brush, and even her tooth rag belonged to Rombol (though she doubted he’d ever ask for the tooth rag back). Having no baggage would make it easier to escape. She would wear her plainest homespun dress when she left the Rake. The Master could have his brocaded finery and all the puffed sleeves.

Supper was a rich rabbit stew. Cymbril hardly heard what the other maidservants said over the steaming bowls. She was daydreaming of Gorhyv Glyn . . . and of the noisome dark of Weepwallow.

After helping with her share of the washing up, Cymbril dressed in the clothes she wore for workdays inside the Rake—a soft white blouse and a durable, dark gray skirt with bodice and shoulder straps. The skirt had three pockets that buttoned closed. Cymbril tucked her two treasures into her top pocket and fastened it.

She waited in her windowless chamber, the candle glowing beside her. At last the deck shuddered, and the Rake began to roll. Her hand trembled as she picked up the candle. She had just turned toward the door when someone knocked.

“Who is it?” she asked, her voice a surprised quaver.

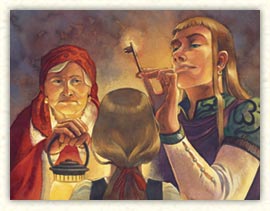

The door opened, and Wiltwain the Overseer peered at her down his long, sharp nose. Mistress Ilda, the head of the maidservants’ gallery, stood a few steps behind him.

“Go to sleep now, Cymbril,” Wiltwain told her. “You’re not to leave your bunk until morning. We are passing through a dangerous region. Master Rombol has ordered a curfew.”

Cymbril felt as if the air had been squeezed out of her. “But—,” she began.

Wiltwain clucked his tongue. “No skulking tonight.” He showed what might have been a knowing smile. Then he searched through the jingling keys at his belt.

He meant to lock her in. In desperation, Cymbril remembered one of Loric’s tactics. “But what if I have to go to the relief closet?”

The Overseer hesitated, glancing from Cymbril to Mistress Ilda. Then he snapped open the ring that held the keys and shook one loose. “I’ll leave this with you, Ilda,” he said.

Mistress Ilda blinked to show that she’d heard him. She very rarely spoke or wasted a single movement of her wrinkled hands or face.

“Into bed now,” said Wiltwain. “Busy day tomorrow. Call Mistress if you need anything.” He pulled the door shut.

Cymbril sank onto the edge of the bed as the key grated in the lock. Click. A silent scream rose inside her, and she threw her pillow against the wall. Outside, the footsteps receded.

Chin in her hands, Cymbril tried to think. “Call Mistress Ilda,” Wiltwain had said. Cymbril was sure calling would get no results. Mistress Ilda was selectively deaf; she heard what she wanted to hear and no more. There was no way out of here. . . . Cymbril would miss the entire journey through Weepwallow. And worse, if they made a habit of locking her in at night, how could she and Loric ever escape?

She was about to change into her nightdress when a thought struck her: after the lock’s click, she hadn’t heard the key slide out again. She crossed to the door and peeped into the keyhole.

Blackness. The key was still in the lock. That was Mistress Ilda’s efficiency—no wasted movement of pocketing the key. In the keyhole, it wouldn’t get lost.

Crouching beside the door, Cymbril set down the candle and listened for a long time. There were no sounds in the hallway. She hurried to her trunk and took out her dark, hooded rain cloak. Carefully she unfolded it and, starting with a corner, slid the hem through the crack under her door. The stiff cloth went smoothly, and she pushed it with her fingers, little by little, until more than half of it lay spread across the planks outside her chamber. Then she unbuttoned her pocket and withdrew the jeweled hairpin. Holding her breath, she pushed the long, skinny end into the keyhole—a perfect fit. When it touched something hard, something that blocked its progress, she gently wiggled it and pushed a little harder.

Clunk!

The key fell onto the cloak outside. Now, if only it had not bounced away . . . if only it would fit beneath the door . . . Slowly, she pulled the cloak back—and the key came with it!

Cymbril whirled to the trunk again, removed an armload of dresses, and arranged them under the bedcovers in a shape that looked like her. Then she put on the cloak, pulled up the hood, and used the key to unlock the door.

She opened it a crack. No one was in the hall, but the night lantern flickered at the bend, giving enough light to see by. Cymbril put her candle onto the bedside stand and blew it out. She eased into the corridor, locked the door, and left the key in the lock.

As quietly as her leather slippers would carry her, she made her way into the Rake’s deep darkness.

At the mouth of the Ferny Way on the top deck, she almost blundered in front of an armored guard who stood like a statue, leaning on his spear. The hallways and decks were deserted; doors normally left open were closed. More torches than usual burned on poles along the deck, driving back shadows. Cymbril had to change her route three times and wriggle behind a row of potted rosebushes.

The cats were out in force tonight, too, slinking around corners and among the roots of hedges. Cymbril stopped to pet the friendlier ones.

Overhead, a ceiling of limbs closed across the thin moon. Cymbril had never seen trees as tall as the Rake; she’d wondered where Rombol had found even the trunks for the craft’s arms, which would only reach from the ground to the lowest rail if stood on end. What had looked like dwarf trees from Ardle’s ridge were unthinkably enormous when seen from the swamp itself, black towers that leaned over the passing city wagon like nosy giants.

Cymbril didn’t hurry toward the bow. She edged among horse barns to the left rail, where the torches were widely spaced. Below, the Rake’s claws rammed through clumps of bushes. Something black and glistening flew in circles around a torch, its wings going thwick-thwick-thwick. Balls of eerie fire rose from the water near and far, pale pink, green, and yellow. Though the Rake followed the driest ground, it also had to avoid the trees; often a wheel sagged into a squishy hole, the decks tilting so steeply that cargo rumbled in the holds.

Crouching beneath a windlass at the rail, Cymbril listened to a guard’s footsteps passing on a balcony above. She watched the fiery globes floating among the roots, bobbing, appearing to spin. They seemed almost alive, fairies or sprites of the swamp.

She couldn’t reach the stairs down to her secret hatchway in the prow—too many guards. Why were so many soldiers about? Did Rombol expect a battle with the trees? The thought wasn’t funny: many of the moss-draped trunks seemed to have grotesque faces.

From the winery’s roof, she’d have a perfect view. When the Rake began to splash through shallow water, Cymbril climbed a lattice grape arbor. Wriggling up onto the slanting roof, she wondered if perhaps she’d carried this idea too far—ropy vines from the swamp’s trees dragged past her, dropping moldy leaves and tiny, many-legged shapes that skittered in all directions. Alone on the roof, she felt unprotected beneath the rotting, breathing ceiling of Weepwallow. She’d just have a look around, then go down to a safer hiding place.

A raised middle section of the roof screened her from the view of anyone in the higher wheelhouse. She rolled to one side, letting a vine slither past, and then crawled forward. Pairs of eyes glinted from forks and holes in the trees. Aside from the cold-looking marsh fires, all the rest was blackness. Loric must be busy indeed tonight.

Cymbril saw the elf boy first, still dressed in patched tunic and trousers. As her chin cleared the roof’s edge, she glimpsed Rombol, Wiltwain, and maybe ten men-at-arms. She pulled her head back quickly before any of them looked up.

Sliding the stone from her pocket, she cupped it in both hands to hide its light and touched it to her forehead. “Loric? Can you hear me?”

I hear you, Cymbril.

Cymbril felt a surge of happiness just to hear his voice again. The strength of the emotion surprised her.

You shouldn’t be here, he said. Especially not up there on the open roof. Rombol shouldn’t have brought us here. There’s danger— He interrupted himself to call a direction to the pilot—a deadfall of limbs and trunks ahead concealed what might be a deep hole under the water. The Rake circled it on the left, trundling off an earth bank at such a pitch that Cymbril flattened herself to keep from sliding. The men below exclaimed and grabbed the rails. In a draft, the torches flared sideways.

When Cymbril could raise her hands to her brow again, she asked, “What danger?”

All this noise, he said. These steel claws gouging and pounding. Old and terrible things sleep here . . . things that ought not to be disturbed.

“The ground is too soft,” Wiltwain said. “The claws are sifting it, not pulling us forward.”

“We need momentum,” said Rombol. “Tell the Armfolk to row harder.”

Wiltwain blew a signal on his shell trumpet, and the Rake’s arms cycled faster.

“No,” said Loric, sounding afraid.

Cymbril raised her head. He was speaking aloud the same words he was thinking, his voice shrill.

“The night’s ear hears us,” Loric gasped, backing as far from the bow as his chain would stretch. “The night’s eye sees us.”

“Keep your eyes open, boy!” Rombol shoved him forward.

Leaves shivered, the laughter, the whispers of the trees. Gnarled and lumpy, the trees loomed like a hostile crowd, an army, pressing closer. Between their slick, fungus-covered trunks, darkness pooled and swirled. . . .

“It’s . . . coming.” Loric dropped to his knees, his arms up as if to shield his head. “It’s coming! It’s HERE!”

Rombol bellowed something, but his words were drowned by a shriek that pierced Cymbril like an icy wind.

Her heart hammered. Clutching the Star Shard against her chest, she whipped around, looking for what had screamed. It had been louder than any human voice.

The cry echoed again, and with it came a heavy flapping of wings. A shape swooped over the Rake, much too large to be a bird. The dismal screech tore from it as it passed, and Cymbril caught a foul smell, worse than waste pits.

Men raised spears or drew swords. Loric cringed against the rail, his ears covered, knees pulled to his chin.

Cymbril pushed the stone into her pocket and squirmed for a clearer view.

“Get under cover!” Loric yelled.

The flying thing perched on a tree limb, its wings flung wide. Torchlight shone on brown feathers mottled with black. Something this big could not possibly be a bird. The body was as broad as a horse’s, its sharp talons as large as an Armfolk’s hand. When Cymbril glimpsed the face, she could not hold back a whimper.

The head was not a bird’s, but that of an ancient woman. Gray hair jutted in filthy spikes. A cruel mouth turned down at the corners. Lips peeled back from jagged teeth in black gums, and the hag-monster shrieked again, its glittering eyes fixed on Cymbril.

“A harpy!” shouted Wiltwain, cuffing the shoulders of the guards. “Stand ready!”

Cymbril had heard tales of harpies, but no words had prepared her for how horrible . . .

The harpy ignored the knot of men. Wings pumping the night air, it launched itself toward Cymbril. The eyes bored into hers, and Cymbril felt frozen in place.

“Cymbril!”

Loric’s cry pulled her gaze away from the monster’s, breaking its spell. As the claws uncurled, reaching for her, she threw herself to the right. The talons narrowly missed her, tearing instead into the boards, planing up ribbons of wood. Wheeling in a tight circle, the harpy screamed in anger.

Cymbril heard the wing beats returning. The harpy would not miss a second time.

Loric leaped to his feet. “Cymbril,” he cried, “jump!”

Cymbril sensed the hideous face behind her, the yellow teeth. As she sprinted forward, harsh screams shook the planks.

It was a long fall to the bow, but she couldn’t hesitate. She picked the biggest target—Rombol—and dove into space.

to be continued

copyright (c) 2008 by Frederic S. Durbin