![]()

The Star Shard

Part 8

by Frederic S. Durbin

by Frederic S. Durbin

illustrated by Emily Fiegenschuh

That evening, when Cymbril managed to linger near Loric’s door, he warned her that they would need the key soon. In three days, the Rake would hold a market in Berryholt, a town above a wooded ravine called the Greenmouth; this was the entrance to Gorhyv Glyn.

Berryholt is small, said Loric in Cymbril’s mind. I’m sure we’ll only be there one day. The best time for escape will be just before dawn on the morning we arrive, after I’m brought back to my room. With any luck, Master Rombol will be in bed.

“If we wait too long,” said Cymbril, “he’ll be up and getting ready.”

Yes. It will have to be precisely timed. When I’m on the bow, Rombol leaves the key with the guards. If we reach the destination before sunrise, the guards take me to my room, lock me in, and slide the key under Rombol’s door.

Cymbril jumped at a scratching sound. But it came from Loric’s room—or more precisely, from his threshold. Through the crack beneath the door, he was pushing out a piece of stiff wire as long as Cymbril’s forearm.

I found this on the ground in Banburnish and put it up my sleeve. It should be just the thing you need.

Cymbril picked up the wire. “For what?”

When the guards leave the key under Rombol’s door, you’ll be hiding nearby. After they’ve gone, you can use this to drag the key back out.

Cymbril’s heart beat faster. “Perfect!”

Hardly perfect. Too much could go wrong. But it’s a chance.

-----

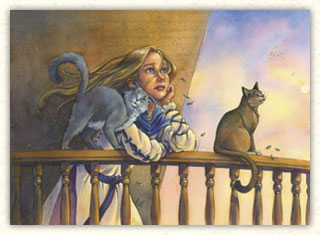

For the next two days, Cymbril’s thoughts whirled like a spring wind, going now in one direction, now in another, full of restless hope and anxiety. At times she felt sadness and regret. As much as she despised the constraints of the Rake, this had been home for almost as long as she could remember. Now that she would be leaving, the mossy alleys seemed more inviting, their ferns alive with intriguing whispers. At breakfast, Miwa the cat rubbed her ankles, and Cymbril felt a pain at the base of her throat. Most of all, of course, she would miss Urrt and the other Urrmsh; she would miss sitting on the floor of the dripping Pushpull Chamber, listening to their soothing songs. How could she say good-bye to Urrt?

Even the Rake’s grand circuit tugged at her heart: the cities and towns under the changing seasons, each far-flung wall built of different stones, the morning light different on each dewy thatch, the breath of each hayfield different in sweetness. Oddly, it was her enslavement that had allowed her to see so much of the world. She thought of the seas of human faces, so rapt when they listened to her singing. Cymbril touched the withered necklace of swamp flowers that the old man in Fencet had given her. She’d hung it on a cloak peg. The dry garland broke beneath her fingers, the petals swirling to the floor.

She knelt and sifted through the dead flowers, thinking of Gorhyv Glyn and what it might be like in the Fey realm. Would she feel freer? Would the Sidhe accept her as one of their own?

After the next day of work in Blue Barrows, she went to see Urrt. She’d thought of a half-dozen ways to bid him farewell, but she used none of them. She sat beside his feet, drew up her knees, and began to weep.

“Ah,” he rumbled, pulling and pushing on the oar. “Yes. We are coming soon to the place you are going, little thrush.” Around them, a long, humming tale went on—or maybe it was a song.

Cymbril hugged his knee and shook as waves of agony she’d never expected rolled through her. Tears spilled from her eyes, and her nose ran.

“Little bird.” Urrt’s palm brushed her hair, gently as the falling of light. “This is a song I’ve not heard from you before. But it is a good song, too, and makes the world better, not worse.”

“I don’t know what to do,” Cymbril gasped when she could. “I thought I knew what I wanted.”

“And so you will,” said Urrt. “Your heart will know. When the time is right, it will tell your head. Have courage.” After a long pause, he added, “Remember the hatch. It will be open tomorrow night.”

Cymbril closed her eyes and rested in the warm space, the Urrmsh voices resonating in the wood, in her bones . . . and the next thing she knew, Urrt was nudging her awake.

“You should go back now,” Urrt told her, “before they miss you up there.”

Cymbril rubbed at her face. It felt stiff with dried tears. She took Urrt’s hand. Panic fluttered in her chest.

“Go on,” Urrt said. “We will talk again soon, I promise you.”

Cymbril took a deep breath, nodded, and hurried to her bunk, afraid to look back.

She tossed through the night, sleeping in snatches, springing awake. Over and over she picked up the stone and the hairpin, the two treasures that no one could take from her. As long as she had these, with their glow of Sidhe fire and magic, she carried a part of her parents. Peering into the Star Shard’s depths, she could almost see the faces of her mother and father, hazy as dreams remembered on waking.

Cymbril was up before dawn and put on her green dress with embroidered leaves on the cape. Her choice of clothing anticipated Gorhyv Glyn, the woodland realm, but it also celebrated summer—the best dress for her last day on the Rake.

The town was Deepdike, named for the mossy trench that circled it, too wide even for a charging horse to leap across, and four fathoms deep. Wooden footbridges spanned it, strong enough to support normal traffic, but the Thunder Rake could not come across to the market square. Instead, a procession of carts and wagons rolled down the ramp and over the bridges.

Cymbril mustered her best efforts, singing with as much passion and conviction as if all the songs told of her own life’s journeys. The ballads brought tears to her listeners’ eyes; the merry songs made them grin.

Then something happened that had never happened before: two minstrels bounded through the crowds, a boy and a girl, both a few scant years older than Cymbril. People laughed and clapped in recognition, thumping the pair on the backs as they passed. Their clothes were patched and of poorer cloth than Cymbril’s, but equally green, as if the three had dressed to match. The boy and the girl appeared just as Cymbril began “Home, Lads, Home.” From the midst of the audience they played along, their fingers flying over the strings of long-necked instruments that hung by straps from their shoulders. As they pounced right up into the wagon bed, one on each side of her, Cymbril stopped in surprise.

“Keep singing!” said the girl. Her black hair hung in a long ponytail, and a spray of faint freckles dotted her face.

Cymbril blinked, forged ahead, and they matched her tune with their own voices, blending into harmony. After her initial bewilderment, Cymbril began to laugh inside, as if she were floating in the sky, sweeping with the birds from cloud to cloud. People in the market began to clap in rhythm, and some linked arms and danced. With three interwoven voices, the part that went “Hey nonny ho nonny hidle didle home” was breathtaking.

When the song ended and the crowd burst into a cacophony of cheers, the minstrels caught Cymbril’s hands and bowed with her. She wanted to collapse and catch her breath, but there was no time—now the requests poured in, and the two paused only to be sure Cymbril knew the next tune.

The sun climbed the sky. Even the merchants came out and stood before their stalls to listen. “You’re doing far too well!” hooted Rombol as the singers huddled together to discuss the words to “Far Green Hills.” The Rake’s Master clanked goblets with the Patron of Deepdike and cupped his free hand around his mouth to shout, “Nobody’s buying a thing!” The crowd laughed with him—but turned quickly back to the wagon as the three began singing again.

When they took a short rest, Cymbril laughed at the way the two flopped down as they pleased, arms and legs all askew. She’d been taught to sit before crowds with composure, like a lady.

The dark-haired girl offered Cymbril a hand to grip in greeting, her arm swinging out in a broad gesture like a man’s. “I’m Bobbin. You have a beautiful voice.”

“Thank you. I’m Cymbril.”

“We know,” said the boy, clasping Cymbril’s hand in turn. “You’re famous.

I’m Argent.” Argent had short, white-blond hair and the faint beginnings of a beard. He wore a small, silver earring.

“We’re cousins,” Bobbin explained, dangling her feet off the wagon bed. “We can’t stay much longer. We’re riding with my uncle to Highcircle.”

Cymbril glanced admiringly at their travel-worn boots, bound up to their knees with leather cords. “You’re not from here,” she said.

“No,” said Argent with a chuckle. “We’re from out there. From everywhere. Like you.”

“You don’t have a home?”

“The grandest home,” said Bobbin. “I own thousands and thousands of magnificent towers, shaded with royal canopies. I call them ‘trees.’ ”

The cousins laughed easily, and Cymbril joined them. She’d never envied the highborn ladies who bought furs and silks at the markets, but she felt something like envy for these two.

Never had Cymbril enjoyed a morning’s market so much. She was sorry when, glancing at the sun’s position, Bobbin and Argent nodded to each other and squeezed Cymbril’s hands again. “That’s it,” Bobbin said. “We ride.”

“It’s been a privilege,” added Argent.

“My privilege,” Cymbril said.

As suddenly as they had appeared, the minstrels hopped down out of the wagon. At a trot, Argent bowed in circles to the crowds, who applauded. Bobbin’s ponytail bounced as she spun and waved. In a blink, they were across the market. They stopped once, however, at the Patron’s booth, and a clerk counted coins into their hands.

The folk of Deepdike weren’t inclined to let Cymbril eat lunch; they were prodders and hair-feelers, leaning too close and breathing on her. Wiltwain rescued her, leading her into the baker’s tent and settling her onto a stool behind a curtain, handing her a tray of hot bannock and blueberry jam.

The afternoon wasn’t easy. The crowds liked her fine as a soloist, but after the fun of the morning, Cymbril couldn’t get her heart back into singing. The world seemed both wondrous and unbearably sad, both cramped and vast. Night was coming. It was as if the air were getting heavier, harder to move through. Have courage, Urrt had said. Hand firmly gripping the treasures in her pocket, Cymbril watched the fireflies winking in the garden plots beyond the square, in the woods across the ditch.

She had just finished “The Evening Bell,” and the thinning crowd was asking for more, when Rombol stood in the square’s center and called, “Roll it up!” Down came the awnings; up rolled the mats. Coin boxes snapped shut and jingled onto high wagon seats. Tents whispered into fallen piles of night. Cymbril stood still in the wagon bed, gazing at the first stars. Tomorrow evening, if all went well, she would be seeing them from the Fey realm.

Though Cymbril wasn’t hungry for the mushroom soup served in the maidservants’ gallery that night, she forced herself to eat well. She would need strength before her next meal. Then, dressed in her faded gray skirt and her oldest white blouse, she went down to see Urrt a final time. This evening she had no tears left.

Urrt smiled when he saw her, as if the world were not such an uncertain place. She sank onto the floorboards beside his feet, and for a long time, neither Cymbril nor Urrt spoke. She was thinking of the countless talks they’d had in the rumbling, humid dark. She’d always felt safe here; the Urrmsh were as permanent as mountains. It seemed to her the Strongarms had somehow transcended grief and pain; they moved the heaviest loads, and yet they were the happiest of creatures. She’d never imagined the evening would come when she could no longer creep down here to find peace.

“Urrt,” she said at last, raising her head.

“Yes, nightingale?”

“Will I see you again?”

“Almost certainly. Has that been troubling you?”

She hadn’t expected such a simple, pleasant answer. “I will?”

He blinked languidly. “I won’t be spending all my life on the Rake, either. Too much to do in the wide world. I have relatives in the Fey country. I’ve visited them before. I’ll visit them again. It won’t be hard finding you, thrush. I’ll just go where the crowds are thickest.”

Cymbril smiled. Urrt was the only one who could always make her smile. Among the Urrmsh, it was easy to believe all the wide roads of life converged in one place, and that it was a happy one. She gazed up at him fondly. As her chin began to tremble, she sprang to her feet. If she didn’t leave the Pushpull Chamber now, it would become impossible. She touched his hand and leaned her head against one enormous arm. “Promise me once more, Urrt, that we’ll talk again. It’s the only way I can walk out of here.”

“Then I promise, Cymbril.”

She looked from his face to those of all the Armfolk she could see, and she backed slowly away. “Thank you all,” she said, not wanting to raise her voice. They waved their hands, chuckled, and kept pushing, pulling, and singing.

“The song is about you,” said one of the Urrmsh beside her as she reached the door. “It has only a beginning so far.”

Cymbril bowed and ran for the stairs.

to be continued

copyright (c) 2009 by Frederic S. Durbin